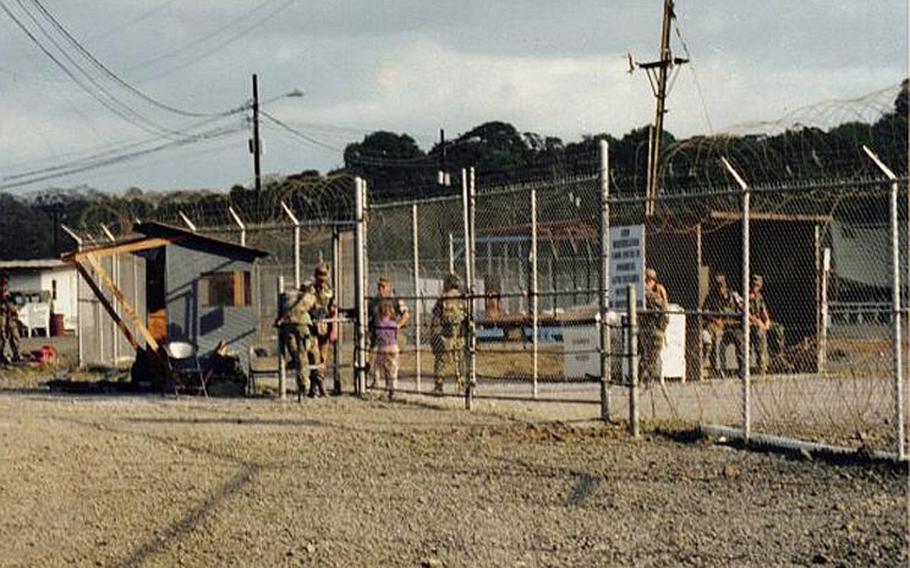

Soldiers gather at the gate of one of the four camps that the U.S. military built to house Cuban refugees in Panama in 1994. On Dec. 8, 1994, hundreds of refugees rioted, throwing thousands of rocks at U.S. soldiers who came inside to quell the disturbance. (Courtesy of Greg Roberts)

Officially it wasn’t even a battle. The U.S. soldiers and the men they fought weren’t even enemies.

But 17 years later, the veterans of this “medieval fight” remember every inch of the battlefield.

“It was just a straight-up brawl,” recalled Sgt. 1st Class Arturo De La Garza, an Army specialist on that day.

Outnumbered more than five to one, the Americans endured 20 unforgiving minutes that seemed like an eternity, unsure if they would emerge alive.

There were no firearms or bombs, just raw, primitive weapons: clubs and shields and, most of all, thousands of baseball-size rocks that shattered the U.S. troops’ bones and rained so densely that the sun seemed blacked out by a sea of stone.

Some of the Americans had seen combat in the Persian Gulf War. Others later fought in Afghanistan and Iraq. Those men almost unanimously agree: Their fight in Panama on Dec. 8, 1994, was the equal in terror and ferocity of anything else they ever faced.

No U.S. troops died that morning. But when they reunited more than a decade later, the U.S. veterans realized they’d all been casualties.

Rocks and batons

Understanding how the men of Company C, 5th Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment fought an unofficial, unnoticed battle in Panama requires a brief history lesson.

In 1994, more Cuban refugees set out for U.S. shores than had tried in a decade, many in rafts and makeshift boats. The U.S. filled the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay with those it caught. Buying time, the U.S. built four large, temporary camps on a military reservation in Panama called Empire Range. The effort was called Operation Safe Haven.

Gen. Barry McCaffrey, 52 at the time, was the four-star commander of U.S. Southern Command. In an interview last week, he said he sympathized with the Cubans, even as it was his job to detain them.

“Our guidance was, [the camps] would be exactly what my grandparents would have hoped to see when they got off the boat at Ellis Island. No guns visible,” McCaffrey said. “We had schools and clinics. … It was a model of how to handle refugees.”

The Cubans lived in large military tents, 100 tents in each camp, built on concrete slabs.

The perimeter of each camp was lined with chain-link fence. There were soccer fields and dining facilities. With so many people living in a wet climate, the ground was covered with rocks to allow water to drain away quickly.

By fall 1994, about 10,000 refugees waited warily at Empire Range. McCaffrey recalled walking through the camps with his wife and talking to them.

“They loved Cuba,” he said, “but they went to the beach, and they put grandmothers and 4-year-old sons [on rafts] to be baked by the sun, [and risk being] eaten by sharks. Why? They wanted freedom.”

‘The sun is gone’

If they had to go into the camp to restore order, U.S. soldiers would be armed only with wooden batons and plexiglass shields.

“We asked for shotguns [with birdshot]. We asked for tear gas. We were told we couldn’t have them,” recalled then-2nd Lt. Jason Amerine, a recent Ranger School graduate who was assigned to Company C’s 1st Platoon. “We weren’t running a concentration camp. We were there to host the Cubans.”

Several times in November and early December, Company C quelled demonstrations. Each time, things died down without violence. On Dec. 7, however, news came down that most of the refugees would be returned to Cuba.

About 500 Cubans rioted inside Camp No. 1. They burned at least one tent, and stole and crashed a military Humvee.

Company C was at Fort Davis, a three-hour drive or 15-minute helicopter flight away from the camps.

“I had just got my tray of food in the cafeteria and sat down, and somebody came into the chow hall and yelled, ‘Charlie Company!’ ” recalled Ryan Epley, then a sergeant with 3rd Platoon. “We were used to getting alerts ... [but] minutes later Chinooks were landing. We ... knew it was business.”

An hour later, at 6 p.m., they were landing at Empire Range.

“Charlie Company had 96 soldiers,” Amerine later recounted in an academic paper about the fight. “The [Air Force Security Police] fielded about 80 airmen. We expected to face between 500 and 1,000 rioters. ... We continued to wield batons, with our shotguns and tear gas locked up at Fort Davis.”

Things quieted down. Company C guarded the camp all night. By mid-morning, a crowd gathered again on the soccer field.

There were two gates to Camp No. 1, both toward the northeast side. The plan was for the Air Force security police to march in from the main gate, while Company C advanced from the side gate. As Company C moved toward the field, its members would force the Cubans toward the dormitory tents.

The soldiers formed up near the dining facility, which blocked their view of the soccer field. About 20 refugees gathered at the gate, wearing masks that they’d made from white T-shirts. They taunted the Americans. A few of the U.S. troops were bilingual. They tried not to laugh at some of the more creative insults.

The sun was hot. An hour passed. A soldier came by with hockey-style shin pads. There weren’t enough for everyone.

Inside the camp, the Cubans tied the gates shut and pushed bleachers from the soccer field against the fence.

“Finally we got the word,” Epley said.

He and two other soldiers went to work on the gate. By now the Cubans were hurling the drainage rocks at the U.S. troops. A few rocks broke through the fence. One of them hit a soldier in the face.

“He got nailed,” Epley recalled. “Broke his jaw.”

They got the gate open slightly, and Epley raced through. He charged at a group of rioters, screaming, with his baton in the air. The sight of the crazed American soldier sent them scurrying.

“Move out!” Amerine yelled.

The Cubans retreated around the corner of the dining facility. Marching three abreast with their riot shields up, as if in a parade, Amerine’s 1st Platoon walked along the back of the dining facility.

As they turned the corner and faced the soccer field, they finally saw what they were facing: hundreds and hundreds of angry rioters.

“The sky filled with a dark cloud of stones,” Amerine wrote later.

Another soldier, Spc. Robert Young, wasn’t far behind. He’d been in the Persian Gulf War and was one of the few combat veterans in the company.

He’d never seen anything like this.

“The sun is gone,” Young recalled. “Thousands and thousands of rocks.”

‘Only one way out’

Company C advanced, with Amerine’s 1st platoon in the lead. A rock struck his unprotected shin.

“Boss, that looks like it hurt,” De La Garza said as Amerine limped forward. Their platoon stayed together, mostly.

Further back, radio operator Greg Roberts didn’t have his own plexiglass shield. Young tried to use his to protect him. The two soldiers, along with the company commander, Capt. Ed Davis, and several other Company C troops, moved toward a big tent the Cubans had used as a chapel.

“Cubans were running along our flanks and grabbing people, beating … them,” Roberts recalled. “You move 50 feet, grab people, pull Cubans off your guys, and keep moving. It was two steps forward, one back the whole time.”

All around them, they saw other soldiers’ riot shields and face masks shattered by the rocks. It was hard to imagine there could be so much stone in the air.

“I looked at Greg Roberts and we had the same look of, ‘We’re not coming out of here alive,’ ” Young recalled. “They’re closing in. Twenty yards, 15 yards, coming from all sides. Another guy ... got his arm broken. Captain Davis, saying let’s get to the front gate. It’s like, ‘Thank God, at least we’re moving. There’s only one way out, and it isn’t going back.’ ”

Young was hit hard in the head with a rock, stunning him. His shield and his face mask shattered.

Amerine was having only slightly better luck. His face shield stayed intact, but each direct hit banged the visor into his face.

“When I watch movies about the Civil War and men marching into fire, that’s what it was,” he recalled. “Everybody was hurt. Everybody got [messed] up.”

His platoon sergeant, Staff Sgt. Jeff Wilson, had a broken arm. One of their squad leaders had a broken leg. He limped along with help from other soldiers.

Now they could see the main gate, and they realized that the Air Force team they were supposed to link up with had been turned back. Behind them, one of Company C’s other platoons had retreated. The rest of the company, more or less, was following.

Subduing the riot by themselves was impossible. First platoon headed toward the main gate. The Cubans couldn’t stop them, but with a seemingly unlimited supply of rocks they could make them pay for every step.

‘Get our guys out’

Finally they reached the gate, but their troubles weren’t over. Either the Air Force or the Cubans — it wasn’t clear which — had locked a chain around it. It opened only enough to let the soldiers through in single file.

Roberts squeezed through, but when he looked back he saw Young, dazed, without his helmet or flak jacket, still inside the camp.

“He was by the gate, sitting on his butt like he didn’t have a care in the world, knocked out with his eyes open,” Roberts said. “Me and Charles Fish, the mortar platoon sergeant, we pulled out Young and a few other guys.”

One of the Cubans stole an American cargo truck, and raced around the camp. He ran over a U.S. soldier, wounding him.

“Another soldier got into a Humvee and T-boned it,” Amerine recalled. “It was pretty cool.”

As De La Garza made his way out the gate, one of his sergeants grabbed him.

“Tell them to stop so we can get our guys out!” the sergeant ordered.

“I looked at him funny,” said De La Garza, a native of Freer, Texas. “My Spanish sucked. I remember putting my hands up and I dropped my baton. In my best ‘Tex-Mex’ I yelled, ‘Hey stop! … You guys kicked our asses! Just let me get my guys out!’ ”

Amerine watched as De La Garza and a few of the other Americans ran back into the camp, faced the deluge again, and pulled their fellow soldiers to safety.

‘You guys lost’

More than 200 U.S. troops were wounded badly enough to be evacuated by helicopter. The riot received only brief mention in U.S. news reports.

Three days later, the battalion teamed with other soldiers, including a Ranger unit under the command of then-Lt. Col. Stanley McChrystal, to reassert control and arrest the ringleaders. Less than half of Amerine’s platoon was healthy enough to participate, but this time they were armed with shotguns and tear gas, and they moved in at 3 a.m. Things went off without a hitch.

A few of the Cuban refugees were granted asylum in the U.S. Others went to Spain. Most were returned to Guantanamo.

In the months that followed, Young, Roberts and Epley got out of the Army. De La Garza moved on to Fort Campbell.

Amerine was set to leave for Korea, and then the Special Forces Qualification Course. Before he left, he wanted to put his soldiers in for decorations.

It wasn’t war, he realized. The Cubans weren’t enemies, and the whole fight had lasted only 20 minutes. But he wanted his troops to get Army Commendation Medals for their bravery. Perhaps De La Garza even deserved the Soldier’s Medal for negotiating under fire and running back into the camp to save other troops.

“You’re acting like this was combat or something,” Amerine recalled one of his commanders saying. “It’s not combat. Besides, you guys lost.”

‘Did this really happen?’

The men of Company C lost touch with each other. For a decade and a half, they hardly talked about it.

Then, Facebook was invented.

“I hadn’t thought about December 8 for a long time,” said Young, but then he connected online with Roberts in 2009 or 2010.

“We picked up like we hadn’t missed a beat,” he said. “Then Amerine pops up on Facebook [and] De La Garza.”

Someone started a Facebook group for Company C veterans. More than 60 members found it. A few started getting together for reunions. One still had a map of the camp.

“That map — all the feelings and all the rush came back,” Young said. “I started comparing … December 8 and my Desert Storm battle. You know what? [Panama] was more intense.”

It turned out, most of the veterans agreed.

“I can tell you that I’ve been in some pretty crazy [stuff] in my life, but going into that Cuban camp was the ... scariest. That was out of control,” said Epley.

De La Garza is a sergeant first class now. He recently put in his papers to retire from the Army in 2012 after 20 years. He did two tours in Iraq, including the initial invasion. As he waited for war in March 2003 he took comfort in knowing he’d been through the experience before.

“At times I was like, did this really happen?” he said. “It was pretty intense.”

Roberts served in Balad, Iraq, in 2009 with the Washington National Guard. Panama, he said, was much worse.

“Inside the camp, on a scale of 1 to 10, I’d give it a 9-plus,” he said. “I’ve never been that scared in my life.

“If there’s anything I watch on TV that freaks me out it’s watching protesters throwing rocks overseas. I’d much rather get shot than rocks thrown at me. It was absolutely terrifying.”

Amerine is now a lieutenant colonel at the Pentagon. He saw combat in Afghanistan in 2001 and led the Special Forces team that brought Afghan President Hamid Karzai into the country.

“When I saw real war later, at times I actually enjoyed it,” he said last week. “Being shot at was actually sometimes amusing. But when people are trying to stone you to death and people are falling and you’re just holding on to each other and marching through it, that’s totally different. It’s just primordial.”

Twitter: @billmurphyjr