()

It was September 1968. The monsoon rains were heavy, making movement in the bush complicated and infinitely more unbearable. Phase 3 of the Tet Offensive was in full swing with rocket and mortar attacks on Danang and Tay Ninh City.

“Attacks by fire” was the primary approach used by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army to deliver their payload of fury. It allowed them to quickly scatter and limit their exposure to friendly return fire from artillery, Tactical Air Command and gunships. Phase 3 of Tet was said to be the weakest of the three phases, with only 15 major attacks across South Vietnam compared to 52 in Phase 2.

This time, Ho Chi Minh took the fight to the countryside, which necessitated a more rural U.S. campaign. One such offensive in Quang Ngai province was Operation Champaign Grove. Beginning Sept. 4, it involved Company A, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Infantry Brigade, Americal Division, and leader of 3rd Platoon, 1st Lt. Raymond James Enners.

Operation Champaign Grove was planned as a relief operation for the Special Forces Civilian Irregular Defense Group camp in Ha Thanh, situated along a strategic supply route that led from the mountains to Quang Ngai City. It was conceived as a three-phase campaign and later was broadened to include search-and-clear operations as the NVA was concentrating its forces in the Song Re Valley south of the Song Tra Khuc “Horseshoe.”

This was no routine company-wide sweep. Enners knew that. Champaign Grove was a brigade-plus operation involving more than 4,500 U.S. infantrymen, along with tactical support units and Army of the Republic of Vietnam fighting elements. Enners focused on the mission and prepared his platoon, as well as himself, applying the skills he learned to the pressing task at hand.

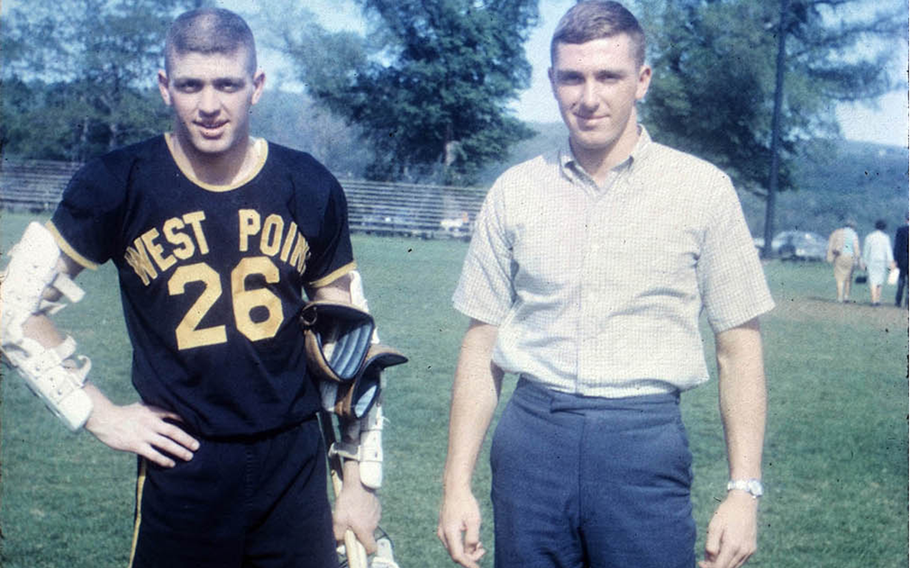

Ray Enners loved to lead. He loved being out front, and his training at West Point and Ranger School provided the confidence to lead his platoon in this operation. Over the course of his life, he met every challenge with intensity, enthusiasm and determination, and this would be no exception.

It was Sept. 18, and after a horrendous firefight the day before near the hamlet of Cao Nguyen, Alpha Company continued its sweep in a southwesterly direction toward Xa Ky Mao. Enners’ platoon, on point, came across a large rice paddy with a tree line to the north. Squad Leader Sgt. Alfred Matheson was the “slack man” — usually the second man in order of march behind the point man — as 3rd Platoon crossed at the narrow point in the paddies and maneuvered around a finger of trees.

Heading west, they hugged the tree line for about 75 meters. The point man suddenly stopped. He whispered to Matheson that he heard something five meters inside the thicket. Matheson gave the “halt” signal and peered toward the thick brush. The platoon dropped to one knee with rifles at the ready.

No more than 10 seconds later, the NVA opened up with six-, seven- and eight-round bursts of AK-47 fire. The point man dove behind the nearest paddy dike. Matheson’s M16 flew out of his hands. He was hit in the right elbow and fell. The tree line exploded with RPD machine gun and automatic weapons fire from the NVA. The 3rd Platoon responded with M16 and M79 fire blasting the tree line. The NVA was dug in and well camouflaged.

Matheson called for help as the six-inch gash in his right elbow bled profusely. He sought the scant cover of a nearby dike so the NVA couldn’t see him. Enemy automatic weapons fire intensified.

Under a hail of bullets, Enners crawled forward from 100 meters back and reached Matheson’s squad. He tried twice to reach the wounded squad leader, but the enemy fire was relentless. He repositioned his three squads. Sgt. 1st Class William Wright of 2nd Platoon maneuvered two M60s around the finger of trees, to support Enners’ attempt to rescue Matheson.

Fear lost its grip ‒ the radio crackled, “I’m moving!” An intense barrage of M60s, M16s and M79 grenade launchers ripped into the tree line; the sound deafening. Matheson bent back toward the rear of the dike and saw Enners jump over a drop-off in a crouched position with his left arm extended. As Matheson extended his left arm, Enners grabbed it and pulled him back to the next drop-off.

Enners then reorganized his men, preparing to attack the thicket. He and Sgt. Kermit Williams moved two squads to the right flank short of the tree line to within 15 meters of the NVA.

A radio transmission stunned Alpha Company. “Three-six is down! Three-six is down!” Enners lay where he was hit, fatally wounded. He was less than two months from his 23rd birthday.

Capt. William Adams called for artillery. For 20 minutes, eight-inch shells pierced the air, targeting the tree line. Suddenly the enemy broke contact and dispersed. Twenty-one NVA soldiers were dead.

During the two-hour firefight, medevac dustoff crews swooped into the grassy area near the rear of the paddies, extracting the wounded. The final extraction lifted off at 2300 hours in route to Duc Pho with Enners’ body on board.

For his actions on that day Enners would receive the Distinguished Service Cross -- America’s second highest military award for valor -- a life extinguished but a legacy born that lives on today.

Epilogue A special breed of person serves in the armed forces. They heed a call to duty, or perhaps a commitment to the ideals of freedom established by our forefathers.

A special breed of soldier serves in combat on the front lines and places themselves in harm’s way to safeguard Americans’ way of life.

There is also a special breed of soldiers who risks their lives for one another, for their unit or for a cause. It is the ultimate act of character, courage and selflessness. It’s a matter of honor, and honor never dies.

Richard W. Enners wrote a book about his brother, Lt. Raymond “Iggy’’ Enners called “Heart of Gray.”

Sources for this article include research for the book, personal recollections, operations reports, daily after-action reports and personal interviews with West Point classmates, coaches and soldiers he served with and commanded.