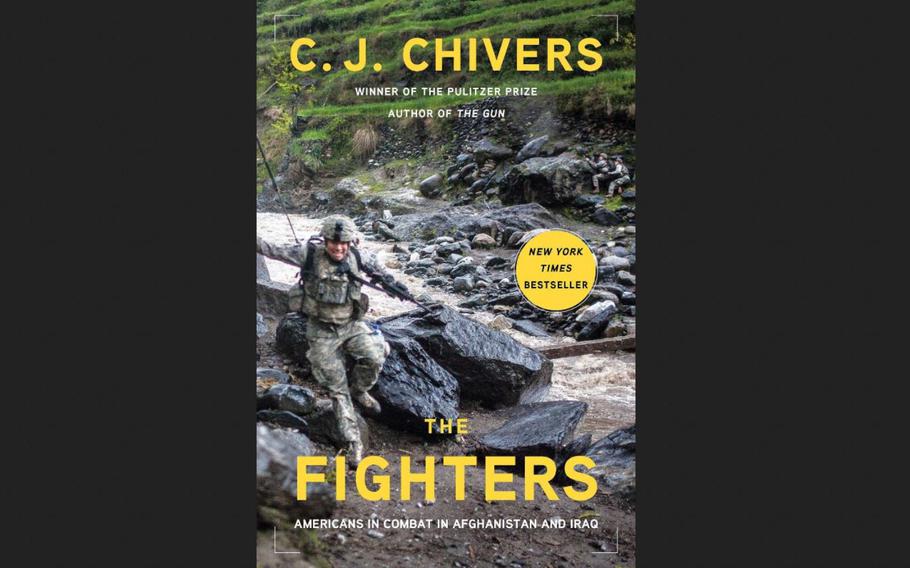

Pictured here is the cover of ''The Fighters: Americans in Combat in Afghanistan and Iraq,'' which features a photograph of an ambush beginning alongside Afghanistan's Korengal River on April 15, 2009, taken by Tyler Hicks of the New York Times. (Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

Veterans on the Post-9/11 G.I. Bill earlier this decade often complained that fellow college students frequently confronted them with the same grim question: “Have you ever killed anyone?”

The question reduced military service to a single dimension, a thing of morbid curiosity, and stymied any discussion of what it meant to have served in Iraq or Afghanistan. For many, it illustrated how little the American public understood about those the country sent to war.

In his new book, “The Fighters: Americans in Combat in Afghanistan and Iraq,” C.J. Chivers pulls back the curtain on some of the more than 2.7 million Americans who served the wars since Sept. 11, 2001. Its title makes plural the name of his Pulitzer Prize-winning 2016 magazine profile of a Marine’s postwar struggle in an Illinois college town, and it exhibits similar deep reporting and sensitive storytelling.

A Marine Corps infantry veteran, Chivers offers detailed chronicles of the journeys endured by those in the lower and middle ranks.

It follows six main characters, some of whom took part in the early days of the wars and returned when they metastasized into counterinsurgencies, and some who joined as idealistic recruits with the wars already well underway.

Chivers reported on broader aspects of these stories as a New York Times war correspondent, but here he fleshes out the troops’ personal experiences with details gleaned from interviews, personal correspondence and other materials.

The preface offers a forceful critique of the wars and how those leading them have failed their subordinates and the public.

In its opening scene, Marine grunts in Afghanistan’s Helmand province tally civilian casualties that they hadn’t caused but were forced to clean up. The Corps was eager to forget the incident, though the Marines themselves would not.

“Many of them wanted then, and still want now, to connect their battlefield service to something greater than a memory reel of gunfights, explosions and grievous wounds,” Chivers writes. “They wanted to understand accidental killings as isolated mistakes in a campaign characterized by sound strategy, moral authority, and lasting success. They didn’t get this, at least not all of it.”

During the 2010 campaign to seize the Taliban stronghold of Marjah, a dozen unarmed civilians had been killed by a pair of U.S. artillery rocket strikes. None of the Marines on the ground had called them in. Chivers long pursued the investigation report into the incident, a footnote tells us, but the Corps said it could not find a copy.

It’s an event Chivers witnessed while embedded, as are several other moments he describes. He returns to Marjah later in the book with one of his main subjects, a Marine platoon leader, for a battle that promised to turn the tide of the war but in the end did not. Marjah would be seized but would eventually fall back into Taliban hands.

The five other main characters are a strike fighter pilot, a Green Beret, a combat medic, a scout helicopter pilot and an enlisted grunt. Filling out much of the rest of the cast are combat troops or those who closely supported them. Many are the grunts who don’t make America’s foreign policy but are “stuck in it,” as Chivers puts it.

The broad criticism of policy and leadership failures gives way to stories mostly focused on events and concerns on a personal scale — a night ambush, an insurgent rocket attack, a sniper’s bullet, a perilous roadway.

When they do consider the bigger picture, the troops here are often perplexed by the strategy or their part in it. Robert Soto, a specialist serving in Afghanistan’s deadly Korengal Valley in 2009, settles on one way to make sense of it.

“We’re here because we’re here,” he decides. “If nothing else, the soldiers could fight for one another. That was something worth fighting for, and with a tangible purpose and a defined end.”

We might wonder if it wasn’t always so for those on the front lines.

There are heartbreaking coincidences and bitter ironies — a deviation from routine proves fatal, a moment of levity becomes shame. There’s also plenty of faith, honor and courage in the face of war’s hazards and horrors, often in tense or exhilarating scenes.

Chivers’ style is spare and understated, making the occasional flourish that much more effective, as when he describes a trio of schoolgirls riding bicycles down a residential street in Powder Springs, Ga., where Dustin Kirby, a once-handsome but now scarred Navy hospital corpsman back from war, is disheveled and burning brush on the family property: “Like a school of fish, they abruptly turned and crossed the opposite side of the street, giving him wide berth.”

Through his focus on the particular, these stories begin to feel universal, representing the wars’ unfathomable costs to so many Americans. These fighters have their foibles, but they are largely competent, self-sacrificing and seeking to do what’s right for their fellow troops. Fatal errors seem to originate from entities unseen or unknown, often at higher echelons, baffling those in harm’s way.

Chivers is unapologetic in his approach — and his focus on the lowly combatant is a cherished tradition that partly echoes the argument for Stars and Stripes’ existence. But I couldn’t help feeling a voice or two from higher up might have rounded out the book.

Still, senior officials and their public affairs staffs have no shortage of chances to speak. What Chivers gives us in “The Fighters” is an uncommonly close look at the personal stories that frequently go untold.

No small part of Chivers’ effort was informed by time he spent embedded alongside his subjects in the fight, a level of media access that has become exceedingly rare in recent years.

As a generation with no memory of a time before 9/11 comes of age to fight in Afghanistan, I can’t help wondering how much more of a mystery their service will be with media embeds brief and infrequent, and America’s attention turned elsewhere.

garland.chad@stripes.comTwitter: @chadgarland