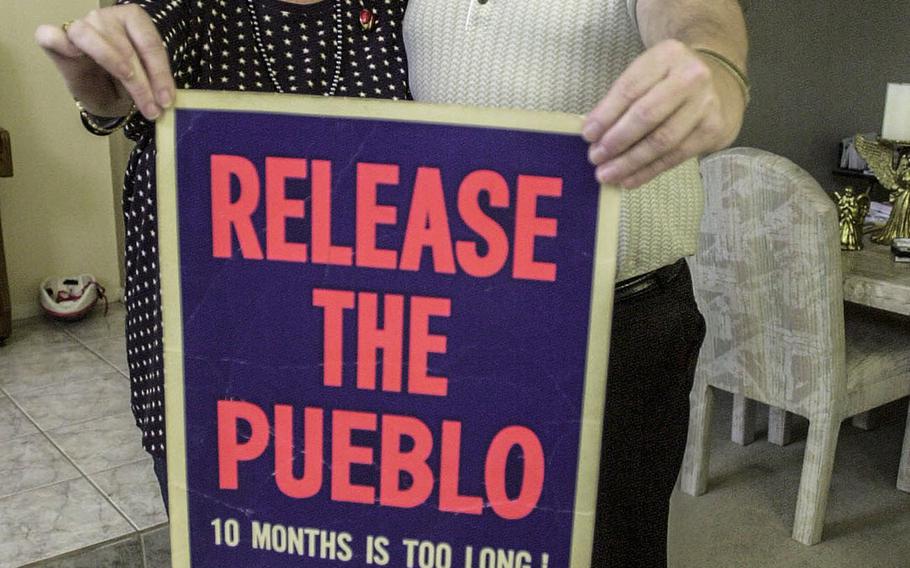

In a February, 2000 photo, Pueblo survivor James Kell and his wife, Pat, hold up a sign from 1968. (Jason Carter/Stars and Stripes)

The wives of the men of the Pueblo endured their own form of torture.

At the time, the military treated family members indifferently and the Department of Defense put up a wall of silence when the wives sought information. The Navy did its best to keep them quiet while telling them almost nothing about their husbands’ fate.

"Every day was torment, every night was torment," said Pat Kell, wife of Chief Petty Officer James Kell. "I was on an emotional roller coaster."

The spy ship Pueblo had been assigned to Yokosuka, Japan, the Navy’s Far East nerve center. Kell, a communications technician, was serving on shore duty at Kamiseya, a communications base south of Tokyo. He signed on to work in the Pueblo’s secret crypto room, the "SOD-hut" in place of another sailor just two days before the ship left. He and Pat figured he’d be gone a month or less.

So Pat stayed behind with their four children, ages 8, 7, 3, and 1½. Eighteen days later, she heard about the seizure of the Pueblo on the radio, which was how many families heard the news. She called the Navy for information, but she could find out nothing.

The initial news reports said one sailor had been killed, but they didn’t say which one. Every wife worried it was her husband.

No one worried more than Carol Murphy, wife of Lt. Edward Murphy, the executive officer. A few days after the seizure, the North Koreans released a photograph showing all the officers — except Murphy. He’d simply been standing someplace else, but she was convinced he was dead.

"(The families) went through hell," Ed Murphy said. "They didn’t know what was happening. We knew."

Pat Kell was one of only 11 Pueblo wives who lived in Japan, and she didn’t know any of the others. Traveling to the Far East in those days was neither easy nor cheap, and no one from her own family came to help her, or even called.

"The kids weren’t old enough to talk to," she said. "I knew I couldn’t allow myself to fall apart. I was the mother and the father."

For a time after the ship’s capture, the Navy would not issue the men’s paychecks. Pat visited a chaplain for help to pay her bills.

She stayed in Japan until the end of March, the last Pueblo wife to leave the country. She and James had loved it there, and she didn’t want to go. But it became clear there would be no quick resolution, and no one knew if Kell or the rest of the crew would come home alive.

The Navy offered to move her wherever she wanted to go. She chose Hawaii because it seemed likely that Jim might be released there. Pat packed for the move herself while taking care of the children.

"I felt like I was giving up by leaving (Japan)," she said. "I was leaving everything I was familiar with, going to a place that was totally unknown to me."

For the wives, rank offered no privileges. Rose Bucher, the wife of Cmdr. Lloyd "Pete" Bucher, the Pueblo’s captain, couldn’t pry any information out of the Navy, either. Since leaving Yokosuka in late 1966, at the end of Pete’s previous posting there, she and her two sons had lived near her family in Jefferson City, Mo.

As the senior officer’s wife, she felt duty-bound to boost morale among the Pueblo families. So she asked the Navy for the addresses of the other wives. They refused to give them.

"The Navy thought I might be a rabble-rouser," she said.

It turns out the Navy was right. By spring, the Pueblo had become lost in the flood of 1968 events — the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, President Johnson’s stunning decision not to seek re-election, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. She concluded the Pueblo Incident had embarrassed the Navy and the government, and securing the crew’s release seemed to have slipped to the back burner.

So she made up a simple bumper sticker that said "Remember the Pueblo." Quiet and self-effacing but fiercely determined, she appeared on "The Mike Douglas Show," a popular afternoon talk show.

Rose held up the bumper sticker on the air. A movement was born.

Soon she and other Pueblo wives spoke regularly with journalists and civic organizations, rode in parades and lobbied congressmen. Even with growing racial unrest, anti-war protests, the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, and the presidential election, the women of the Pueblo kept the ship in the public’s eye.

"I think it really was effective," Rose Bucher says today.

She also tracked down as many of the crew’s families as possible and offered support where she could. One of the women she called was Pat Kell. They formed a friendship that continues to this day.

"She didn’t let me feel like I was high and dry out there," Pat Kell says. "You can be brave to a point, but some time you have to let it out."

Just before Christmas, after 11 long months, the United States issued a sham apology to get the men released. The ecstatic families met their husbands in San Diego.

"It was phenomenal to see them," Pat Kell said. "San Diego opened its heart. It was awesome."

The family required plenty of adjusting once Jim returned home. His health was poor and his children had to adjust to his return — common experiences among Pueblo families.

"It was easier for the older two. The younger two didn’t know who he was," Pat said. "It required some patience on Jimmy’s part."

The friendships with other crew families offer a small silver lining to the Pueblo experience. The Kells and the Buchers still get together frequently, and also meet with some of the many other ex-Pueblo sailors who settled in the San Diego area. For each of them, the Pueblo Incident remains the central experience of their lives.

"We both still have scars from it," Jim Kell said. "I wouldn’t have wished it on anyone else."