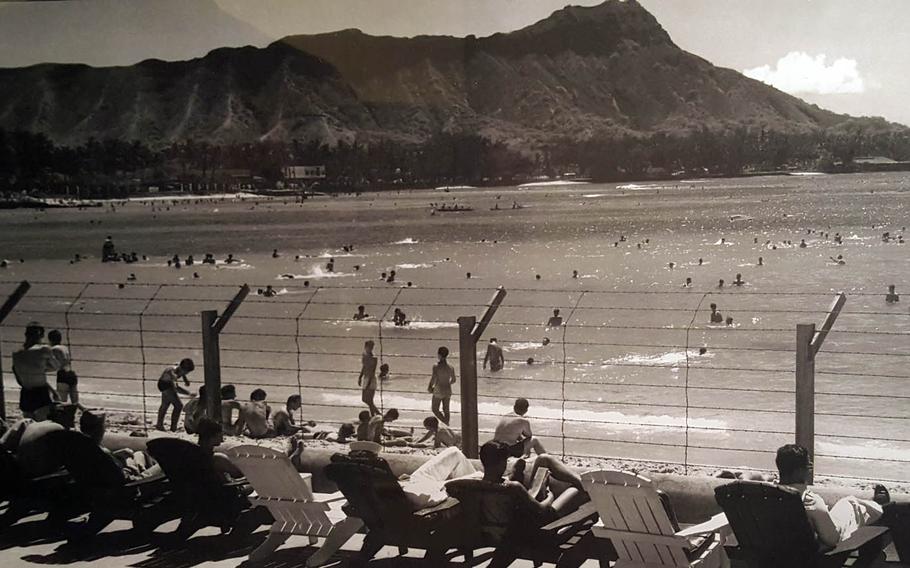

Waikiki Beach on Oahu, Hawaii, was fortified with a barbed-wire fence during World War II in the event of an invasion by the Japanese, as shown in this undated photo now on display at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. (Wyatt Olson/Stars and Stripes)

For the past 75 years, America has annually commemorated Japan’s surprise attack on Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941.

The ceremonies — sometimes modest, sometimes expansive, as in the 50th and 75th anniversaries — mark the lives of the 2,403 Americans who died that day, as well as the valor and suffering of the sailors, Marines and soldiers who fought and lived through the attack.

The retelling usually ends there. But for the people in the Territory of Hawaii, it was the beginning of a period of martial law that curtailed the lifestyle and liberties of Hawaiians in a way not experienced by Americans living on the mainland.

“Homefront Hawaii,” a simple exhibit at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, provides a glimpse into that post-attack period with photos, artifacts and a dose of music from the day by way of a 1940s-era radio.

Immediately after the attack, Joseph B. Poindexter, Hawaii’s territorial governor, declared martial law, and National Guard members took control of the cities. It was believed that the surprise attack was just the prelude to a full-scale invasion of Oahu, and the military and citizenry set about fortifying the island for such an onslaught.

But martial law was also a reaction to the perceived threat by the presence of roughly 150,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans living in the territory, which represented about 35 percent of the population.

Despite that suspicion, fewer than 2,000 of them were ultimately sent to internment camps, a ratio far less than were imprisoned in mainland states.

Freedom for Hawaiians not placed in camps, however, was severely curtailed by the suspension of constitutional protections in order to “discourage concerted action of any kind,” the military governor said at the time. Those rights remained suspended for almost three years and were reinstated only after numerous challenges in court.

A strict curfew barred anyone from being on the streets between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. — and people of Japanese descent had to be in their homes by 8 p.m.

Everyone older than age 6 was fingerprinted, registered and required to carry military-issued identification cards. The military maintained intelligence reports on a vast number of Hawaiian residents.

On display at the exhibit are original and replicas of identification documents, such as the ID certificate of Kikuno Nakamoto, a citizen of Japan, which notes a “scar on forehead” as a visible mark.

Examples of curfew passes are also displayed, which were issued to those who had to be on the streets after hours.

Censorship became a way of life in Hawaii during the war years. Newspapers required licenses to operate, and no publication was allowed to be printed in any language other than English. The telephone company was commandeered by the military, and all mail was read and censored.

Islanders were ordered to construct bomb shelters.

Photographs at the exhibit show men digging trenches in downtown Honolulu. One photo shows beachgoers at Waikiki cavorting near a 10-foot-tall barbed-wire fence spanning the length of the beach.

Nights were dark indeed during that period because a “blackout” order required all civilian lights — whether bulbs or flames — to be extinguished at nightfall. Doors and windows of residences were required to be covered; car headlights had to be painted a dark color to dim them.

While most Hawaiians experienced the same feeling of common cause as mainlanders in defeating the Axis threat, opposition to martial law began to grow in the wake of the U.S. victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, after which a Japanese invasion of Hawaii became unlikely.

Some aspects of martial law were eased in 1943, with civilian government agencies resuming control of many functions and trial by jury resuming for local and federal laws.

Martial law ended Oct. 24, 1944. In 1946, the Supreme Court ruled that the suspension of civilian courts had not been justified by law.

The exhibit quotes resident Manual Lemes as saying: “If I were asked what was the worst experience I had all through this war, my answer would be: martial law!’

“Homefront Hawaii” DIRECTIONS

The exhibit can be seen on the first floor of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, Portico Hall in the Hawaiian Hall Complex, 1525 Bernice St., Honolulu.

TIMES

9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily through March 1

COSTS

$22.95 adults; $19.95 adults with military ID; $19.95 seniors; $14.95 ages 4-12; free for ages 3 and younger. Museum-lot parking is $5 per car.

INFORMATION

Phone: (808) 847-3511; website: www.bishopmuseum.org/exhibits