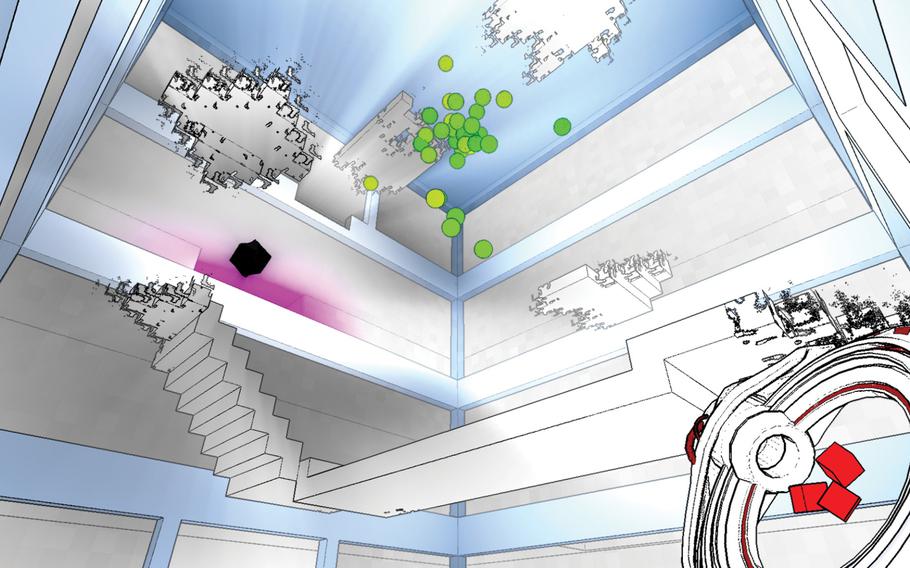

Antichamber uses hot colors and shapes to fill what's otherwise a whitewashed world without textures. (Game screenshot)

You’re greeted by two sets of stairs. One, lit brightly in neon red, going down, while the other, going up, glows a garish blue. Which do you take? In books or movies, characters get just one choice. The blue pill or the red one. In games, players take both paths — poking upstairs to see if there are any goodies to grab, then backtracking for more exploring.

In “Antichamber,” a new first-person puzzle indie game on PC, the correct answer is to take neither.

That’s not because the game is bad, or either option is dull, it’s because both of these obvious options, like hundreds of others throughout “Antichamber,” lead you right where you came from.

This game, with its non-Euclidian shapes, tricks and shifting corridors, is an experiment that would make your high school geometry teacher pull her hair out. The flat side of a cube can turn into a hallway; walls reform or disappear; four lefts never lead in a circle; and the simple act of looking through a window can alter the constructs of a room.

“Antichamber” is a hall of mirrors wrapped in a kaleidoscope, twisted around like a Rubik’s Cube. But oddly enough, its rules are easier to describe on paper than to understand in the game. Uncovering this world’s logic is a process equally mystifying and maddening — but also very rewarding (in the above scenario, the correct thing to do is to turn around and go back the way you came in, which has mysteriously formed a new path).

Along the hallways of this psychological puzzler is an assortment of strange word clues, block puzzles and neon-colored walls. Apart from those elements, the game is almost devoid of detail. No walls, floors or ceilings have any texture — they’re merely flat surfaces and shapes. And the game’s soundtrack is just as scattershot as its architecture. Sometimes you hear a feverish drum beat, other times rainfall or pigeons cooing. None of it is tied to what you’re seeing on-screen, but is still oddly helpful — creating audio associations to certain rooms or actions you should perform.

“Antichamber” conjures up the simplicity of many older, iconic PC games. Its warping walls and shifting floors are much like the haunted, confusing corridors of “Doom.” It gives us that totally-on-your-own puzzle style of “Myst.” And its reliance, eventually, on a tool to help you manipulate blocks to solve spatial puzzles harkens back to “Portal.”

But while a player could rely on a certain thematic consistency in those games, “Antichamber” is more interested in showing you random objects and shapes than tying anything together in some cohesive way.

In an odd way, all of the nonstop absurdity becomes familiar after a while. You stop trusting things on screen. You assume that in each new area, the game is trying to trick you. The sooner you accept that, the quicker the puzzles start to unfold.

There’s not a lot of story here. It’s left to you to make sense of why you’re trapped in these Escher-inspired staircases and contiguous, nonsensical paths. In the few areas that aren’t completely barren, odd sculptures depicting human emotions, simple shapes or ticking clocks are on display.

Perhaps this random assortment has some deeper meaning that designer Alexander Bruce had in mind, but mostly it serves to reinforce the chaotic randomness. By the time the game ends, in one violent but muted, colorless final act, you’re so detached from the worries of a normal game that it seems completely OK that you might be in some kind of danger. You might have put all the final pieces together, but it was all a dream anyway. Fittingly, the game shut itself down after completion, like a dream you can’t remember after waking up.

None of the plot problems really matter in the face of what “Antichamber” accomplishes, though. Far too many games try to simulate reality. “Antichamber” is a testament to what games can accomplish when they make up their own rules.

Bottom line: If you’ve been seeking a game that takes both the red and blue pill, this is your chance.

Platform: PC

Online: antichamber-game.com