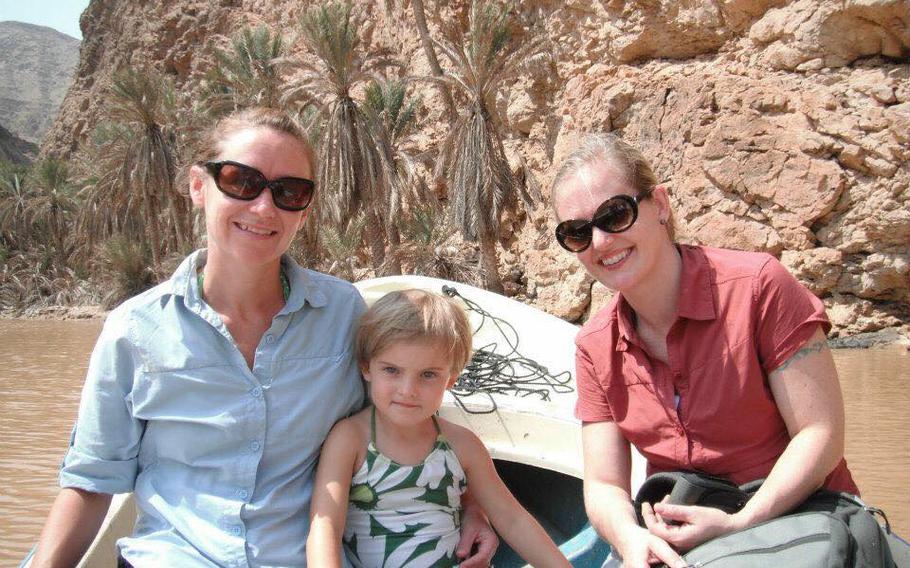

A better trip: Katie Monge; Maeve Evans and Siobhan Fallon in Wadi Shab, Oman, in 2011. (Courtesy of Siobhan Fallon)

About 10 years ago, when my husband was deployed to Iraq, a senior officer’s wife held a meeting to update the spouses on what was happening in Baghdad. At the end of the night, she stood at the community center door and handed out magnets that said, “Put On Your Big Girl Panties!”

The second I read that cheery script, I loathed that piece of plastic. I wanted to stomp out into the parking lot and throw it as far as possible, preferably through the windshield of the commander’s wife’s SUV. I understood the sentiment behind it, how she wanted to impart an empowering message of self-reliance upon us — to emphasize that we could handle the flat tires and bill paying and children’s manic birthday parties without the presence or aid of our faraway soldiers — but to me it implied we were a bunch of coddled toddlers in diapers. However, I smiled and said “Thank you.” I later used it to pin my grocery list to my fridge and soon lost it during our next military move.

A few years later, in 2011, my family and I were stationed in Amman, Jordan, at the United States embassy. Not two weeks after we arrived, my husband was unexpectedly sent to help support NATO missions in Italy.

Now, I wasn’t alone. I had the embassy community. And I had a military spouse friend, Katie, whose husband also deployed. Katie was much more fearless and “big-girl panties” than me. For example, she would go jogging. In a place where most of the women wore long abayas that covered them from wrist to ankle, not to mention hijab veils to conceal their hair, Katie would wear short-sleeved t-shirts. Sometimes she even wore shorts. She ignored the taxis that honked as she jogged past, or the men who stared, mouths agape, at those naked and lean female limbs.

I was nervous about living in the Middle East. I was nervous about driving in new places. I was nervous about not speaking Arabic. I was nervous about everything. Katie gave me a pep talk. She said I needed to get out of my pajamas, leave my apartment, and go sightseeing! Travel the country! Be adventurous! Let’s show those husbands what we can do!

So I agreed, if only to have something to tell my spouse when I spoke to him next, rather than my usual passive aggressive whining about how ‘funny’ it was that he had brought me and my daughter to Jordan and then promptly left us there to go to Europe.

We decided to take a day trip to Ajloun to see the 12th-century castle built by the nephew of the great Saladin. I would drive since my 3-year-old’s car seat was latched into our new Land Rover. Let me rephrase: the used Land Rover my husband had bought from a German guy he met at a bar.

We set out for Ajloun in the late morning. We brought a few water bottles and some halal marshmallows and a bag of copyright infringement snacks called Crunchy Stuff that looked and tasted exactly like Cheetos. It was only 75 kilometers away! Three American blondes in an ancient land in an ancient Land Rover. What could go wrong?

I was proud. I was fearless. I was driving! The random speed bumps, the goats and chickens unexpectedly dodging across the road, the poorly signed highways and drivers who cut us off, none of it stopped me. Whose got the big girl panties on now, bitches?

After about an hour of ascent, just when we could see the castle high on the hill above, the car stopped accelerating.

I pulled over.

Smoke started billowing from the hood. There was the smell of burning rubber, of everything bad you never want your car to smell like. I parked on what should have been an overlook, perched high with a view of the fertile valley below, but looked more like a garbage dump, with crushed water bottles, plastic bags and dirty diapers.

It was March and there had been sleet a few nights earlier, but that day was sunny and clear. We got out of the car and let my daughter do some ballet moves while Katie and I tried not to panic. I lifted up the hood as if I knew what I was doing. Katie called a few friends, but none of them could come and get us.

So I called the United States Embassy in Amman.

I dialed the Marine guard unit that is the quick reaction force that protects the embassy, and the young man who answered the phone, after ascertaining that I was not under an immediate terrorist attack, kindly transferred me to a much less kind warrant officer who told me it was a weekend, he was with his family, and, though he did not actually say this outright, that I was an idiot. But he called someone, who called someone, who maybe called someone else, and a mechanic named Mohammed with a smattering of English called me back.

“Drive to Ajloun,” I told him. “You’ll see my black Land Rover on the hill to the castle. We have yellow hair.” Without asking for any more information, he said he was coming for us.

When I hung up, Katie and I assessed where we were, on the edge of what seemed to be a small, rundown town.

That’s when we noticed a man sitting on a white plastic chair, 20 yards away, watching us. I waved my hand tentatively in his direction, but he did not wave back.

A moment later, two boys came out from a cement block building. They were around 11 years old, wearing dirty, too-small sweaters, the sleeves frayed. “Cash money?” they called out as they drew near.

“I’m sorry, we don’t have any,” we said, smiling. Jordanian hospitality is legendary. We thought the boys would help us, perhaps bring us back to their parents’ homes, and at least let my daughter use their bathroom.

“Cash money?” Their voices grew louder. We apologized, unsure how to play along, and turned our pockets inside out.

That’s when the sermon from the mosque across the street started to echo through the loudspeakers perched from its minaret. We couldn’t understand the loud staccato Arabic of the iman, but the voice sounded angry, rapid fire, and it was easy to imagine him railing against the influences of the West, or blond women sashaying around in running shorts. My daughter wasn’t spinning any more. She took my hand, speechless and staring. I got her back in the car. Katie tried some of her newly learned Arabic on the boys, but they continue to shout, hands out, and she got into the car too.

We locked the doors and waved goodbye as if we were about to continue on our pleasant drive north, pretending our car didn’t reek of horrible burnt car things. The boys started to knock on the windows. Katie, frustrated, reached up and slammed her own palm on the glass. “No money!” she shouted. Katie was a teacher. Katie understood kids. The boys walked away. We smiled at each other. Katie had won!

But then they started to throw rocks. The man in the chair continued to sit motionless, not lifting a finger to stop them or help us in any way. We could tell the boys were throwing small rocks, not heavy enough to crack glass. But the stones were big enough that we were afraid to get out of the car and chase them away.

So we just sat there and waited for Mohammed.

We ignored the boys, drank our water, ate the Crunchy Stuff, read one book over and over again to my daughter. The boys would alternatively throw rocks and then flop down in the dirt and peer at us, then throw some more rocks. It was nearly an hour before they got bored enough to leave.

Finally, a small silver hatchback pulled over in front of my car. Two young men stepped out gingerly, dressed as if on their way to a club. One had a shaved head and tight yellow t-shirt while the other wore a blue button up shirt, dark jeans, leather loafers, his hair a mess of dark curls. The dark-haired man came to the car, introduced himself in rough English as the long-awaited Mohammed, and then poked around under my hood for a few minutes in much the same way I had earlier.

They had no tools. No rags. No water. Little English.

They did not look like mechanics. But they also did not look like killers.

They walked across the street to the man on a folding chair, and returned with a big plastic bottle of water.

“Very good luck!” Mohammed said happily. “That man is mechanic!”

He convinced us to get into their silver hatchback, which Katie agreed to drive. I unlatched my daughter’s car seat and shoved it into his car, strapping my daughter in precariously. They managed to get my Land Rover going; fortunately, it was a downhill coast back to Amman. We pulled over every few miles to fill my radiator with water.

We followed them into the mechanic quarter of the city, full of garages and gutted cars. Locks on rusted metal doors. It looked like the perfect place to keep three American hostages. All the signs were in Arabic, and there was no one around, certainly not any Westerners. I started to take photos of everything with my digital camera just in case they murdered us, but also because I knew there was no way I would ever be able to find this place again in order to pick up my car.

Mohammed put my Land Rover in one of the garages, and then came over to us, motioning for Katie to get into the back seat with me. Katie did so. Then he drove us to my apartment, told me he would fix my car as soon as possible, God willing, Inshallah.

We were home. We were safe.

For a long time, when I thought of that day, I remembered my fear. How I was a useless, hapless American whose only plan of action was to lock herself in her car and wait. I was ashamed of myself for not chasing those boys away, for not trying to talk to that man (THAT MECHANIC!) on the chair, for not wearing big-girl panties.

But recently I’ve come to think that maybe that commander’s wife would have thought we did OK. Big-girl panties or not, there are situations you cannot get yourself out of alone. Maybe there are times when wearing your big-girl panties means reaching out. Katie and I relied on each other, but it was Mohammed, a kind and decent stranger, who charged a fair price and didn’t add an extra penny for the hours he spent rescuing us on his holy day and one day off a week. It was Mohammed who came to our rescue.

So maybe there are times to be self-reliant, and times when a person needs support. There are times when you lock your car doors, and times when you open them. Times when you give a strange man the keys to your Land Rover and climb into his silver hatchback, then follow him down into the heart of an unknown city.

There are times when your only option is trust. There are moments when the very best friend you have might be a stranger who barely speaks your language.

There are times when the wisest thing to do is to let someone help you.

Siobhan Fallon’s new novel, “The Confusion of Languages,” about two military spouses who find themselves navigating cultural miscommunications in Jordan during the Arab Spring, will be released in paperback by Putnam/Penguin this June. She is also the author of the award-winning story collection about Fort Hood, “You Know When the Men Are Gone.” Fallon and her family are currently stationed in the United Arab Emirates, where her husband is an Army officer with the American Embassy of Abu Dhabi.