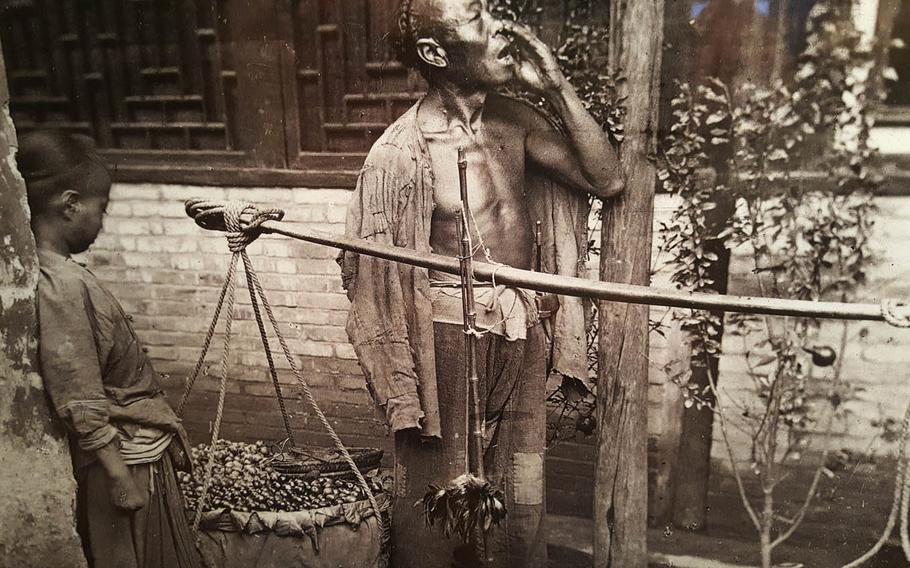

A fruit-seller beckons customers in Beijing in this photo taken by John Thomson during his 1871-72 trip to China. The photo is now on display at the East-West Center Gallery in Honolulu. (Wyatt Olson/Stars and Stripes)

When I moved to China in 2006 to teach journalism at a university, I went sight unseen. The images I’d conjured of the country beforehand were of pagodas, qipao dresses, rickshaws and the two-stringed erhu.

What I found, however, were drab concrete buildings, mass-market sneakers and jeans, waves of motorbikes and K-pop.

My stereotypes were almost a century out of date, fostered in part by Hollywood and the travel industry. Indeed, China itself has gone to great lengths to nurture this anachronistic image, having entirely rebuilt portions of the Great Wall — where nothing of the original remains — purely for tourism.

This is why the current East-West Center exhibit of photographs taken in China about 150 years ago is so compelling. “China through the Lens of John Thomson 1869-1872” offers up enlargements of about 50 photographs from the dawn of the art form’s invention, taken by a pioneer of photojournalism. It’s a look back at China before industrialization, before communism, before tourism.

Thomson, a Scotsman, was one of the first photographers to document China, having developed a fascination for Asia during his initial trip in 1862.

While photography existed in China at the time, the style was rigid and subjects were the high and mighty. Thomson, on the other hand, endeavored to capture all aspects of culture, architecture, landscape and, particularly, the people — even the peasants, who would have rarely been photographed.

In that early era of photography, negatives were made on glass plates rather than the lighter and more durable plastic film to come. Thomson had to travel with bulky equipment for processing the photographs, including a mobile darkroom.

A collection of about 600 of Thomson’s glass negatives ended up at the Wellcome Library collection in London after his death in 1921, and the China photos now being shown at the East-West Center Gallery are from the collection.

Some of the photos on display have been reproduced onto canvasses as large as 5 feet square, making portraits life-size. Most portraits are posed, a reflection no doubt of the difficulty in getting a well-focused shot on moving subjects with early photography equipment.

Mandarin officials — bureaucrats who ran day-to-day operations for the Qing Dynasty — posed in a particular manner that they believed comported the dignity and status of their office. One portrait shows an official from the southern city of Guangzhou looking directly into the camera, face serious but not grim.

But Thomson used a technique for this portrait called “chiaroscuro,” whereby the right half of the official’s face is slightly shadowed, an “art technique unacceptable for portraiture in China at the time,” a placard beside the photos states.

More interesting are the photographs that don’t appear to be posed. One, titled “A Traveling Fruit Seller,” taken in Beijing during Thomson’s 1871-72 trip to that region, shows a fruit vendor, literally dressed in rags, shouting out to draw customers. For the moment, he has removed the yoke from his shoulders and placed the tandem baskets of fruit on the ground. Beside him stands a youngster, seemingly eying the tasty produce.

Another photograph shows the bare feet of two women from the southern province of Fujian. One has been deformed from binding, a painful practice common during the dynastic periods intended to make a woman’s feet short and narrow, an appearance that projected a woman’s status.

Thomas had tried and failed many times to convince women with bound feet to allow him to photograph them. He at last found two women — one with bound feet and one with undamaged feet for comparison — to pose for a picture, but only after paying both women “handsomely” for the opportunity, according to a placard by the photograph.

Landscape photos reveal the kind of traditional architecture that has now been almost entirely demolished from China’s cities. One particularly nice shot is of a caravan of camels in Beijing standing in front of a tiled-roof courtyard.

Thomson watched about 2,000 camels laden with tea depart from Beijing to Russia as he photographed that day.