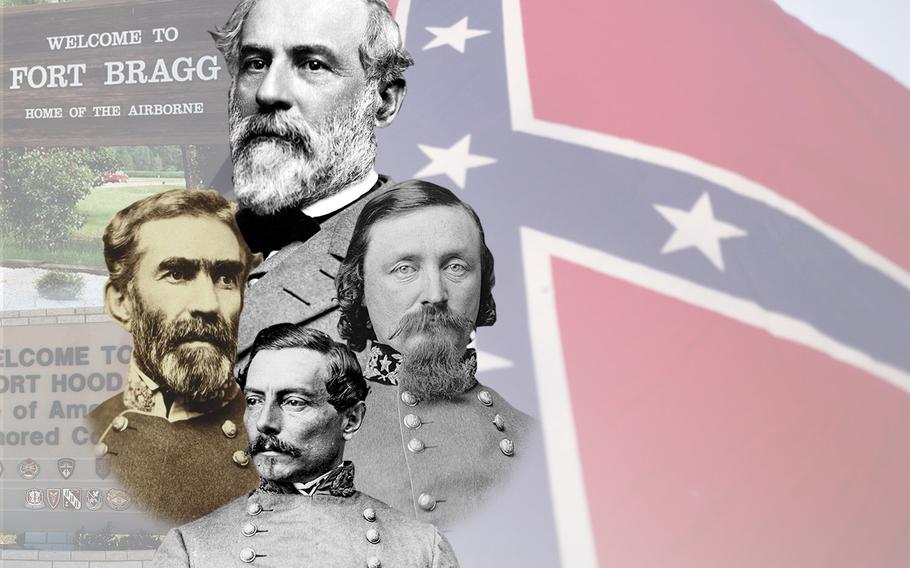

(Illustration by Christopher Six/Stars and Stripes)

Some of the most important U.S. Army bases in the country — including forts Hood, Bragg, Benning, Gordon and Polk — are named for Confederate officers, nearly all slaveholders and one generally acknowledged to have been a leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

Few soldiers, let alone civilians, are aware of the origins of the names of the bases where they live and work.

Some who do, particularly African-Americans, feel insulted.

The propriety of paying homage to men who fought under the rebel flag is coming under renewed scrutiny after the racially motivated killing of nine black worshippers in a historic Charleston, S.C., church. Calls to banish the Confederate flag from the South Carolina Capitol grounds have turned into a national movement to strip symbols of the Confederacy from public parks and buildings, license plates, stores and more.

To many, the names of 10 Army bases should be reviewed as well.

Clarence Sasser, who was awarded the Medal of Honor as a medic in Vietnam, went through basic training at Fort Polk, La., named for Confederate Gen. Leonidas Polk, who was an Episcopal bishop and wealthy slave owner. To Sasser, the name was a slap in the face. It represented, he said, “that I’m not as good as you.”

“When you’re looking back, it’s hard to see where it really matters,” Sasser said in a 2012 phone interview from his home in Houston. “Except for a little bit of the soul.”

Some of the bases were named for men who not only fought against the U.S. Army but also espoused strong views in support of slavery and white supremacy.

Henry Benning, for whom Fort Benning, Ga., is named, warned that the end of slavery would lead to black governors, juries, legislatures and more.

“Is it to be supposed that the white race will stand for that?” Benning wrote before the war. “We will be overpowered and our men will be compelled to wander like vagabonds all over the earth, and as for our women, the horrors of their state we cannot contemplate in imagination.”

Fort Gordon, Ga., home of the Army Signal Corps and Signal Center, honors John Brown Gordon, who rallied fellow Southerners to secede from the Union. In an 1860 speech he proclaimed: “African slavery is the mightiest engine in the universe for the civilization, elevation and refinement of mankind — the surest guarantee of the continuance of liberty among ourselves.”

“Then let us do our duty, protect our liberties, and leave the consequences with God … Do this, and the day is not far distant when the southern Flag shall be omnipotent from the Gulf of Panama to the coast of Delaware; when Cuba shall be ours; when the western breeze shall kiss our flag, as it floats in triumph from the gilded turrets of Mexico’s capital; when the well-clad, well-fed, southern, Christian slave shall nightly beat his tambourine and banjo.”

Gordon would become one of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s most trusted generals, and after the war, he served as a U.S. senator and governor of Georgia. He is also widely believed to have been a founder of the Ku Klux Klan in his home state.

Over the years, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People has decried the base names.

“It is offensive, to say the least, to those African-American troops putting their lives on the line now for the security of our great nation to be trained and housed in facilities named for those who believed that they should not be viewed as citizens, as those who are treated as less than human beings,” Hilary Shelton, director of the NAACP’s Washington, D.C., bureau said in 2012.

Retired Sgt. Maj. D.W. Allen said he was “appalled” to find that Fort Lee, Va., was named for Confederate commander Gen. Robert E. Lee when he served there early in his 25-year career.

“That we would celebrate, in essence, the hideousness that they did and what they stood for. It’s not the American way,” he said. “To think that in this day and age that we are still recognizing these slave-owning generals is appalling to me as a black American. We need to re-evaluate what we stand for.”

Apart from the residual pain of slavery, Jamie Malanowski, a journalist who has written on the Civil War, wrote that it was inappropriate to name military bases for men who led troops who killed U.S. Army soldiers.

“We simply should not name U.S. Army bases after people who fought the U.S. Army in battle,” Malanowski wrote in a widely published 2013 op-ed. “The gesture honors one man, while it denigrates the struggle and the sacrifice of every U.S. soldier who faced him. It mocks them. It mocks the Union they preserved.”

The Army’s chief of public affairs spokesman on Wednesday said there were no plans to review the base names.

“Every Army installation is named for a soldier who holds a place in our military history,” Brig. Gen. Malcolm Frost said in an emailed statement. “Accordingly, these historic names represent individuals, not causes or ideologies. It should be noted that the naming occurred in the spirit of reconciliation, not division.”

The notion of honoring Confederates as well as those who fought to save the Union arose decades after the war as a step toward national reconciliation.

In his book “Cities of the Dead: Contesting the Memory of the Civil War in the South 1865-1914,” historian William Blair wrote that reconciliation between Northern and Southern whites came about after the late 19-century rehabilitation of the Confederate veteran, who began to be hailed as a hero motivated by a love of liberty and distanced from association with slavery.

That corresponded with the rise of Jim Crow rule and African-American disenfranchisement in an emboldened, white-dominated South.

Any move to rename the bases is likely to draw strong opposition, especially among Southern whites.

Even an effort in 2002 to rename a stretch of highway at the Washington-Canadian border named for Confederate President Jefferson Davis was unsuccessful.

EXPLORE | Confederate generals and US Army bases

An online questionnaire by Stars and Stripes found that about 88 percent of more than 18,000 respondents opposed changing the names. Many of them considered changing the names a needless bow to political correctness or an insult to those they consider national heroes.

“Why rewrite history? Historically good leadership doesn’t change just because the Confederate flag is no longer in vogue and offensive to some. I am sure that these posts were named for these generals as a token of reuniting the country after the great civil war ... Why change that?” Walter Buck, a professor at the Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Parker, Colo., wrote to Stars and Stripes.

The bases were established and named by the War Department — in the early 1900s and early 1940s — to train huge numbers of soldiers before the country’s entry into both world wars. At the time, the armed services were segregated, and African-Americans were given the most menial duties.

The War Department sought installations in the South, where land was cheap and where the mild climate meant training could proceed during most months of the year. Racial segregation was also the law of the land there. Those charged with choosing names looked for “distinguished military veterans,” according to the Army’s Center for Military History. Sometimes they consulted local officials, all of them white, asking whom they’d like honored.

“Back in 1940, people in the South had a very favorable view of Southern lore,” said Fred Adolphus, director of the Fort Polk Museum. “The U.S. Army at the time, they felt the same way. Everyone loved the Civil War and Confederate heroes.”

Adolphus declined to weigh in on the issue of whether the Confederate names were still appropriate.

“That’s for the Army to decide,” he told Stars and Stripes on Wednesday. He said that in the era when the names were chosen, “it was not done maliciously or with any rancor.”

Ironically, some of the Confederate generals with bases named after them are considered by military historians to have been less than competent commanders. Two Confederate commanders whom history has judged among the best — Gen. James Longstreet and Gen. Joseph E. Johnston — have no bases named after them.

After the war, Longstreet, whom Lee called “my old war horse,” joined the Republican Party, endorsed Ulysses S. Grant for president and, in 1874, fought for the Reconstruction government against thousands of “White League” insurrectionists in a battle in New Orleans that was not put down until federal troops were called in.

Johnston, whose military prowess was criticized by Confederate officials but praised by his Union opponents, died of pneumonia contracted after serving as a pallbearer at the funeral of the Union general to whom he surrendered, William Tecumseh Sherman.

One of the Confederacy’s most skillful generals, Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, had a base named after him but it has since been closed. The former slave trader-turned-raider known as “The Wizard of the Saddle,” Forrest was also accused of massacring captured black Union soldiers. He was an early member — some say founder — of the Ku Klux Klan. Camp Forrest, Tenn., was established in 1941 and became one of the Army’s largest training bases before it was closed in 1946.

Nevertheless, the nationwide backlash to Confederate symbols after the Charleston massacre may lead to a review of the base names.

In Charleston, the board of visitors of the Citadel, South Carolina’s 173-year-old military academy that sent alumni to the Confederate army, voted to ask the state legislature to remove the Confederate Naval Jack from the campus chapel.

A statement on the college website said a Citadel graduate and relatives of six college employees were killed in the church attack.