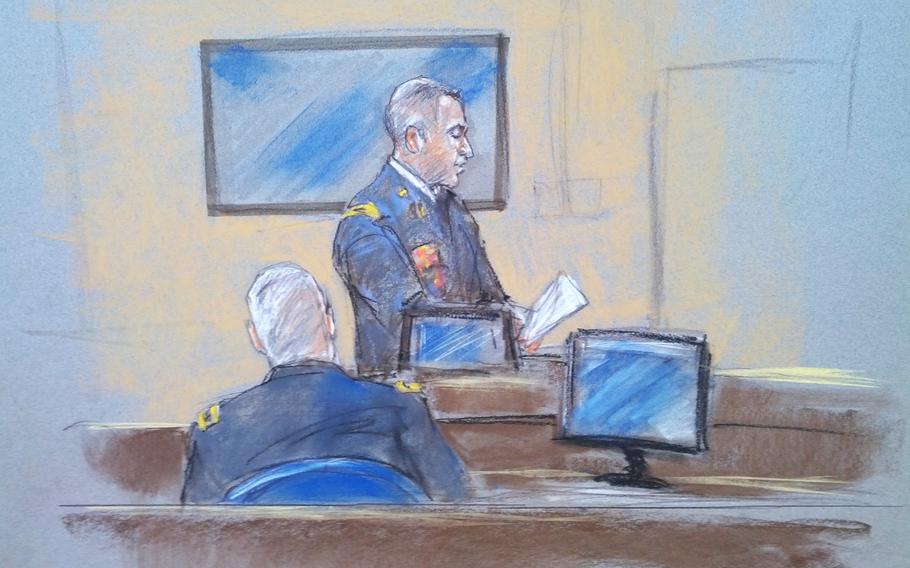

In this sketch by courtroom artist Brigitte Woolsey, prosecutor Maj. Larry Downend reads a statement by Sgt. Mark Todd to the panel of military officers acting as a jury in the case against Maj. Nidal Hasan. Todd is reportedly unable to speak due to a medical condition. (Stars and Stripes)

FORT HOOD, Texas — Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan, the Army psychiatrist charged with the 2009 mass shooting at a pre-deployment clinic here, rested his case Wednesday without calling any witnesses.

Hasan is charged with 13 specifications of premeditated murder and 32 specifications of attempted premeditated murder in the Nov. 5, 2009, massacre. He has chosen to represent himself and could be sentenced to death if convicted.

Still, the panel of 13 military officers acting as a jury in the case could be instructed that they can consider lesser charges against Hasan. Judge Col. Tara Osborn asked the prosecution to prepare a new worksheet for jurors, though she has not ruled on whether the jury will be allowed to consider the lesser offenses.

The discussion prompted the prosecution to ask the judge to dismiss the jury for the rest of the day, and while Osborn was visibly irritated by the request, she granted it.

Hasan opened the court-martial with a brief statement admitting his guilt and has sat quietly in his wheelchair for most of the trial, rarely objecting and choosing to cross-examine only a few of the 89 prosecution witnesses. The American-born Muslim appeared frail and very pale throughout the trial, wearing a sweater under his Army camouflage uniform and putting on a fleece hat during breaks in the proceedings.

Hasan was shot by police after the massacre and is paralyzed.

Osborn had instructed the prosecution to make sure that two men Hasan had added to a witness list were at the courthouse and available to testify, though Hasan said he did not plan to call Tim Jon Semmerling or Lewis Rambo. Semmerling is a death penalty mitigation expert, and Rambo is a research professor of psychology and religion.

Retired Maj. Gen. John Altenburg, a former Army deputy judge advocate general who now practices as an attorney in Washington, D.C., said he was not surprised Hasan elected not to mount a defense.

“I don’t think he wants to be cross-examined, because what he says won’t hold together under cross-examination,” he said.

Hasan will be able to make an unsworn statement about his actions without cross-examination during the penalty phase of the trial, Altenberg said.

There are two likely rationales for Hasan’s decision to not defend himself, Altenberg said.

“Either he simply wants the death penalty because he thinks it will make him a martyr and he wants to get there quicker, or perhaps he thinks if he just lays back, either the government or the judge will make some kind of error and it will be reversible on appeal,” he said.

Lisa Windsor, a retired Army colonel who served as a military lawyer for 22 years and now works for the law firm Tully Rinckey LLC, said she wasn’t certain whether Hasan would take the stand in his own defense, but she hoped he would.

“I think the panel wants to hear from him. I think they want to hear why he did it,” Windsor said. “I think everybody wants to know why this officer … all of the sudden decides to do something so heinous.”

Hasan will have a chance to present a closing statement Thursday.

While some –- including Hasan’s standby defense counsel –- have said they believe Hasan is actively seeking the death penalty, Windsor said she doesn’t see that.

“I don’t think the way he has presented himself in the media or the trial has suggested that,” she said.

His decision not to question most of the witnesses could be his way of exhibiting remorse; he may not want to face them or he may not want to re-traumatize them, Windsor said.

Eugene Fidell, a visiting lecturer at Yale Law School and co-founder and former president of National Institute of Military Justice, said it’s difficult to tell whether Hasan is trying to be put to death.

“A normal person,” Fidell said, would want to be acquitted or at least avoid the death penalty. Hasan is “not in that category,” he said.

“Once you grasp the fact that Hasan is playing according to a different rulebook, it all makes sense and none of it makes sense. It’s an absurd exercise,” Fidell said.

For Hasan to be sentenced to death, the jury must vote unanimously to convict him on all charges, must agree that aggravating factors are present and not outweighed by mitigating factors, and vote for the death penalty.

Hasan would be transferred to the military’s death row, at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., while his case is automatically appealed to the Army Court of Criminal Appeals, Windsor said. After that Hasan could appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces or to the Supreme Court, she said.

The appeals process could take years.

Because the votes must be unanimous, there’s a strong possibility Hasan could escape lethal injection, Altenberg said.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if there were at least one or two court members who say, ‘Why should I give this guy what he wants, if he wants to be a martyr? I’d rather see this guy spend the rest of his life in jail than give him what he wants,’” he said.

Fidell acknowledged that “anything could happen,” but said he believes Hasan will get the death penalty.

“If I were a betting man, I would say that people will not take that counterintuitive approach,” he said.

Chris Carroll contributed to this report.

hlad.jennifer@stripes.com Twitter: @jhlad