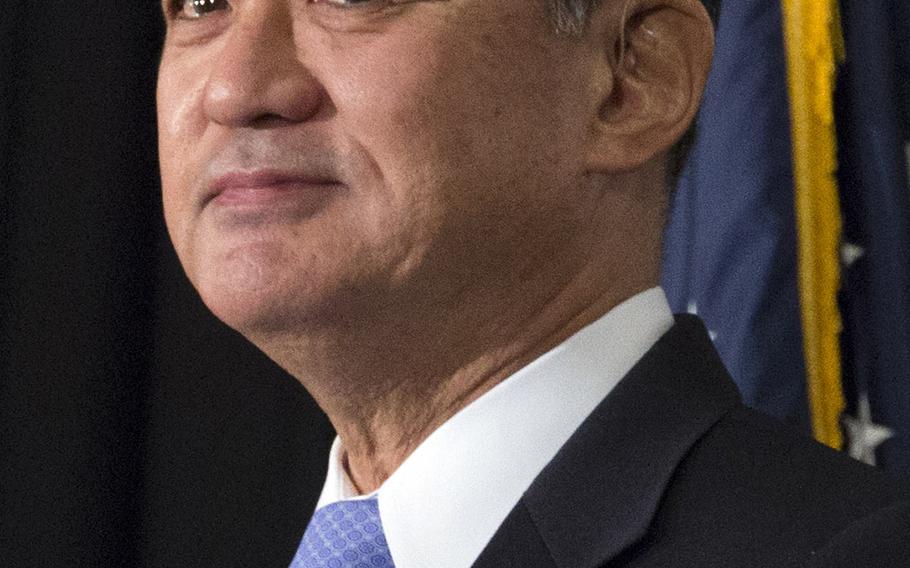

Veterans Affairs Secretary Eric Shinseki, shortly before his resignation was announced on May 30, 2014. (Chris Carroll/Stars and Stripes)

WASHINGTON — Veterans Affairs Secretary Eric Shinseki has long endured criticism for being too quiet as a leader who wasn’t out front on important issues.

That demeanor, and those criticisms, might well have contributed to his decision to resign.

Rep. Jeff Miller, R-Fla., chairman of the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, has been among the harshest critics of Shinseki and the VA. On Friday, he called Shinseki an “honorable man” but said he deserved to be removed from the department.

Shinseki’s tenure “will forever be tainted by a pervasive lack of accountability among poorly performing VA employees and managers, apparent widespread corruption among medical center officials and an unparalleled lack of transparency with Congress, the public and the press,” Miller said in a statement.

The staff surrounding the secretary, who shielded him from the facts of the deep department problems, should also be punished, he said.

“Nearly every member of Shinseki’s inner circle failed him in a major way,” Miller said.

In testimony last week on secret waiting lists, generally poor care at VA facilities and a lack of accountability at every level, Shinseki showed none of the fire lawmakers had hoped to see from a man who said he was “mad as hell” about the unfolding revelations.

The Boston Globe has called him “a quiet leader at a time when veterans need a persistent public nuisance.” Time magazine said his reticence shows “he lacks the creativity and leadership skills” needed for his post.

The 71-year-old Vietnam War veteran disagreed.

“I’m not somebody easily frustrated,” he told Stars and Stripes in 2013. “I know what I have to do. And what I have to do is serve veterans better than they’re being served today.”

On June 30, Shinseki became the longest serving secretary in VA history and the longest-serving leader of federal veterans programs since the Vietnam War.

But with the problems the department faces, the question has always been whether his style could translate to action.

Promises and progress

Shinseki took over as VA secretary amid President Barack Obama’s promises to end the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and to bring tens of thousands of new veterans back home.

Obama’s first 100 days included three bold mandates for Shinseki: End the benefits backlog, end veteran homelessness, and enable seamless sharing of medical records between the defense and veterans affairs departments.

On the homelessness front, outreach efforts have pulled about 15,000 veterans off the streets in recent years. According to a 2013 annual report by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, while there has been a 25 percent reduction in the ranks of the veteran homeless, some 57,000 remain.

VA officials insisted in 2013 that they would have seamless sharing of basic medical records between DOD and the VA in place by the end of the year. But Shinseki and Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel were on Capitol Hill on Tuesday briefing senators — they have yet to create the system prescribed by Congress in 2008.

And on the benefits backlog. the VA reported March 31 that that the number of claims in processing for more than 125 days had dropped to 344,000, compared with a high of about 611,000 in March 2013, though veterans groups have at times expressed doubts about how the numbers are tabulated.

These issues and the report out of the Phoenix VA that perhaps 40 veterans died after being put on a secret waiting list moved the American Legion to call for Shinseki, along with two top lieutenants to resign.

Reluctant in the spotlight

Supporters insist that Shinseki’s own humility and calm demeanor has allowed others to craft an image of him as aloof or out-of-touch.

“He has a deep and unbounded commitment to the troops he took into battle and the troops he fought with,” said former VA deputy secretary Scott Gould, who worked beside Shinseki for four years. “He remembers these are guys he sent into battle himself.”

Shinkseki has visited VA facilities in all 50 states, delivering pep talks to workers and progress briefings to local officials. At a recent visit with employees in Detroit, he discussed technical details of the department’s new claims processing software.

He served 38 years as a soldier, rising from the poor son of Japanese immigrants in Hawaii to the Army’s 34th Chief of Staff. He frequently lapses into military conversation and talks a lot about “the kids” he’s responsible for — the staffers working the backlog problem today, the soldiers he sent to war in Afghanistan, “the kids I went to war with in Vietnam.”

Shinseki was wounded three times in that war. The first time was mortar shrapnel in his face and chest, the second was a broken arm in a helicopter crash. The third time, a land mine blew off most of his right foot.

Support among his ‘troops’

Leaders from the American Legion and Disabled American Veterans had been outspoken in their support for Shinseki, calling him the most responsive and focused VA administrator in recent memory. DAV officials labeled the top VA post “the most thankless job in Washington” and noted that Shinseki has “dedicated his life to military service,” even in his post-military life.

Shinseki meets with the five biggest veterans service organizations on a monthly basis. Attendees reported honest exchanges about problems and concerns the groups are having. The secretary also meets regularly with a host of other veterans advocates, offering the same top-level access on their priorities.

VA officials have added about 1 million more veterans to their benefits and health care rolls over the last four years, a mark of outreach that Shinseki notes proudly. One of the reasons for the backlog problem has been the flood of applications from new and old veterans, which VA staffers argue indicates a growing faith that the system can help improve their lives.

His statements about fixing the VA have been called optimistic even by his supporters, and naive be his detractors. Still he views his job as a military mission, with concrete goals and tight time lines.

He acknowledged to Stars and Stripes that he and the department haven’t done a good job persuading outsiders to adopt that optimism.

When asked about his role as a nationwide voice for veterans, he defers. “Could I do this better? Absolutely. I’m not an expert on this.”

That point is not lost on many of his critics, who ask whether an accomplished soldier, even one dedicated to his job, is the best choice as CEO of an enormous health care system.

“I serve at the pleasure of the president,” he said when asked that question by Stars and Stripes, one he repeated to Congress at his grilling on May 22.

The president has decided to make a change.