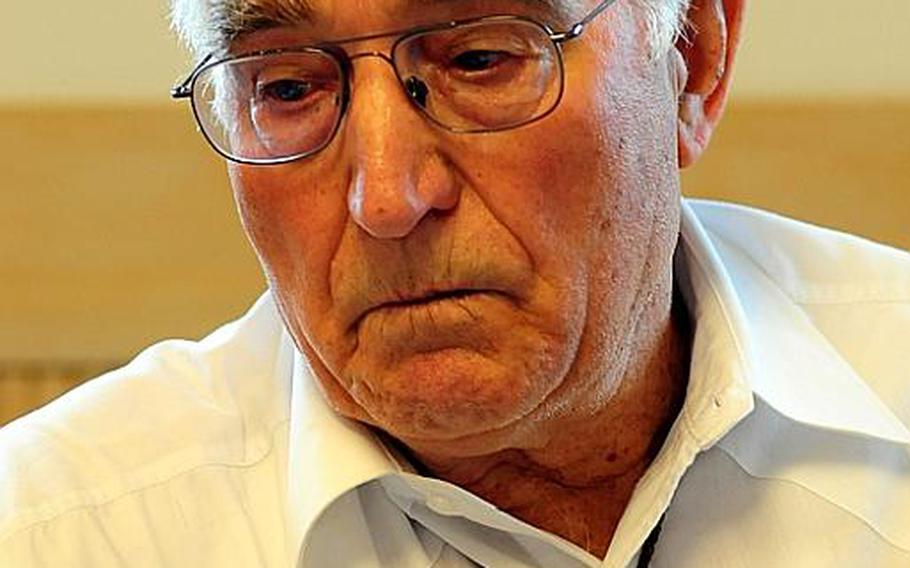

Durl Gibbs recently flew to Okinawa with his son Wes to return a wallet he took from a dead Japanese soldier. He hoped to return the wallet, which contained many photos, to the relatives of the soldier. (Matt Orr/Stars and Stripes)

ITOMAN, Okinawa – Durl Gibbs took the wallet from a Japanese soldier who was killed in front of him during the Battle of Okinawa.

It remained with Gibbs for the next 65-plus years. So did the war.

Now at age 85, he wants to return the wallet and its contents to the family of the slain soldier. He traveled to Okinawa this week from his Montana home with his son, Wes, in hope of locating the family.

“I don’t know why I picked up the wallet,” Gibbs said Friday at the Okinawa Peace Memorial Museum in Itoman, a few miles from where he fought on Mount Yoza.

In mid-June of 1945 during final stages of the 83-day battle, Gibbs, a private fresh out of high school, was in the thick of things with the 381st Infantry Regiment, 3rd Battalion, I company. About 110,000 Japanese troops and Okinawa conscripts and more than 150,000 Okinawa civilians died during the fight for the island. More than 14,000 Americans were killed in what would be the last major land battle of the Pacific war.

“We were in foxholes, two men in each hole,” Gibbs said, recalling how he and his partner would take turns standing watch so the other could rest during the night.

“We had just changed and I got to the bottom of the hole to rest when my buddy saw a Japanese soldier walking up toward us,” he said.

Gibbs said the last thing they wanted to do was give their position away by firing a shot.

“So my buddy and the enemy had hand-to-hand combat,” he said.

When Gibbs got to the top of the hole, the Japanese soldier was dead.

It was an event that occurred a lifetime ago, but his wet eyes tell that it never left him, even after being discharged from the Army and fulfilling his dream of becoming a rancher in Montana.

The next morning Gibbs saw the fallen enemy had a pistol.

“I got the pistol and, probably with a souvenir on my mind, I picked up the wallet,” he said.

“I couldn’t figure out why I did that,” he said of taking the brown leather wallet that contained a dozen photographs and a small white envelope containing hair and clipped finger nails.

The envelope said “Army Sgt. Keijiro Hojo, Akatsuki the 1674th Unit,” with his personal seal on it. One of the photographs had a name and home address on the back. Another photo had written on the back: “My younger brother, died in a battle in the Pacific, April 1, 1943.”

Gibbs said that when he started to raise his own family — he has two sons and a daughter — he realized how important those photos would be to the slain soldier’s family.

The pistol had been stolen when he returned stateside, but he never let go of wallet.

“They must be wondering what happened to him,” he said of the soldier, whom he called a hero. “He paid the ultimate sacrifice for his country.”

Shizuo “Alex” Kishaba of the Ryukyu American Historical Research Society, who is trying to help Gibbs locate the family, said the wallet is believed to belong to Hojo, whose hair and clipped nails was among the photographs. It was customary in those days for Japanese soldiers to carry samples of hair and nails as a form of identification in case of their deaths, Kishaba said. Kishaba sent a query to the Association for War-Bereaved Families in Iwate prefecture in northern Japan, where Hojo’s hometown is.

Gibbs was to depart the island Saturday, leaving the care of the wallet and its contents with the Ryukyu American Historical Research Society.

“It shouldn’t take more than one week before we can locate the family,” said Kishaba of the society, who is renowned for its efforts in recovering and restoring lost Ryukuan cultural artifacts taken from Okinawa in the aftermath of the battle.

“I hope this will [provide] closure for his family, as well as for me,” Gibbs said.